idle gaze 073: satire, the great cultural sedative.

Is irony a powerful form of creative subversion? Or a complacent coping mechanism?

This essay was originally published in the third issue of

, a print-only magazine featuring writing and conversations exploring the creative industries, this time through the lens of freedom. You can order a copy online or grab at a decent magazine stockist soon near you.Sometime in the future, when we look back at the twenty-twenties, I think we’ll reminisce about an era when creative expression felt more dynamic and entertaining than ever. We’ll remember a decade where we mastered a powerful form of artistic ammunition which involved our ability to combine comedy and critique in masterful ways to question the status quo. And perhaps we wouldn’t be wrong, these could very well be the golden days of satire – that delicate yet potent weapon forged from equal parts humour and social consciousness. The all-revealing mirror, reflecting the collective absurdities of this strange and surreal time back at us.

For starters, take a look at all the ‘eat the rich’ entertainment on our screens: an abundance of films and shows that expose the glaring gap between the rich and poor, haves and have-nots. A time when productions like White Lotus and The Menu have become watercooler moments, drawing our attention to the oblivious entitlement and performative social awareness of wealthy resort guests and Michelin-star snobs. This is indeed the height of social class schadenfreude, where films like Bong Joon-ho's Parasite and Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness – darkly comedic meditations on the fragility of social hierarchies – win hearts, minds, and awards like no other.

And while quick-witted subversion can be a scathingly sharp tool, like any blade wielded too frequently and eagerly against every surface that presents itself, it gradually loses its capacity to cleave through what truly matters. Don’t get me wrong – I think satire plays an immensely important role today in how we create and consume culture. Nothing can quite so effectively pierce the veil of power structures otherwise hidden in plain sight. However, I worry that we’ll look back at this as a time when everything in art, music, fashion, and entertainment became so steeped in comedic irony that creative expression began to lose its bite.

Let’s revisit the ‘eat the rich’ genre as an example – a phenomenon that reached fever pitch in the last decade. Today, we engage in class critique more than ever. Yet herein lies the ironic truth: no matter how loudly we mock, laugh at, and curse the elite, nothing changes. There is no revolution or revolt in sight. As

observed in an article in New York Magazine a few years ago: “Never in human history have we possessed so capacious a knowledge of the various and specific iniquities of the world — and so little hope of them ever being rectified.”Across culture, we’re seeing the same trend: an overabundance of satire that reveals the problem underneath, but a deficit of agency to actually tackle it. The frontlines of fashion were once places where perceptions and norms could be legitimately changed, rather than merely acknowledged as an inescapable reality. In the 1970s, Vivienne Westwood challenged class structures and authority through her punk collections, while Yves Saint Laurent's Le Smoking line introduced the first women's tuxedo suit, challenging gender ‘rules’ in formal wear. In the 1990s, designers like Stella McCartney fought for sustainable and cruelty-free garments, eventually cementing the use of real fur as a faux pas.

I can’t help but juxtapose these pioneering, convention-breaking movements with the satire-drenched fashion industry of today, where it seems like everyone is committing to a bit and nothing is ever serious. From Balenciaga’s tongue-in-cheek €2,000 IKEA FRAKTA shopping bag dupes to e-commerce platform Ssense’s self-deprecating takes on the absurdity of fashion subculture elitism, the runway sometimes feels reduced to one big meme generator.

The critic Roy Christopher once famously called irony “the most abused trope of our time, a ‘get out of judgment free’ card, an escape route, an exit strategy.” But perhaps it's no surprise that we have become conditioned to avoid – rather than face – reality head-on. Millennials, Gen Z, and Gen A have all had to adopt their own unique flavours of irony as a coping mechanism; a way to psychologically shelter themselves from the constant hardships and guaranteed failures of modern life.

It’s quite telling that the most successful artists of our era are the ones who have learnt to speak the language of self-referential depreciation fluently – as a means to engage with the fans of today – even when they want to say something earnest. Charli XCX's Brat wrestled with complex themes like motherhood, ageing, and grief. But Charli’s team knew very well that these big, thorny questions had to be wrapped in layer upon layer of irony – low resolution, slime green promo material and terminally online TikTok marketing – to achieve breakthrough popularity.

Unsurprisingly, many creatives find this fear of sincerity frustrating. Musician Ethel Cain ranted on Tumblr last year about how “nobody takes anything seriously anymore”, exasperated by the fact that her debut album, Preacher’s Daughter, a harrowing tale of sexual assault, domestic captivity, and murder, was so often reduced by her fans to worn-out online memes and predictable jokes.

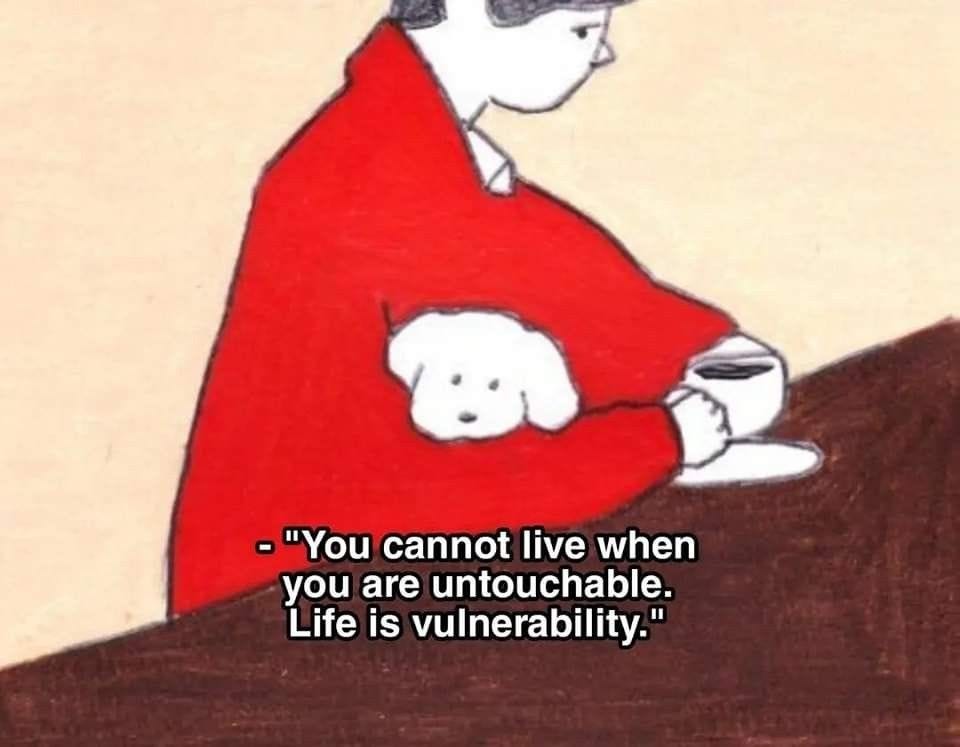

She’s not wrong. In this irony epidemic, I fear we’re losing more than just the ability to be serious. We’re losing the capacity to sincerely engage – not just with art, but with life. When satire has become the great collective sedative of the modern creative era, we are on some level lobotomised, unable to truly connect with the rough edges of humanity. Sometimes, things are serious. Not everything needs to be turned into a joke. It’s important to remember that some of the sharpest, most imaginative forms of self-expression can emerge when we resist the urge to constantly caricature and poke fun at the world, instead embracing earnest expression in all its raw, vulnerable glory.

ps this essay appears in the Playground print alongside beautiful illustrations by Hugo Sundkvist.

Brilliant as always. Thank you for sharing your mind with us.