idle gaze 056: anaesthetised and aestheticised.

the emotional numbing and visual repackaging of spiky subcultures.

This year, the road into Burning Man was temporarily halted by climate protesters, blocking the road with a 28-foot trailer, causing a bumper-to-bumper traffic jam for over an hour. It disrupted the plans for some 80,000 people in RVs hauling trailers, who were making their annual pilgrimage across the dusty tendrils of Nevada's Black Rock Desert to their beloved countercultural bacchanal.

The protestors consisted of a coalition of activists representing the climate groups Extinction Rebellion, Rave Revolution, and Scientist Rebellion – demanding that Burning Man ban private jets and single-use plastics, as well as unlimited generator and propane use. They clashed with the masses of outraged attendees, angered by the disruption to their yearly outing to the playa.

It was clear that the event goers would not empathise with the cause of the protestors. The ‘Burners’ appeared more concerned with pursuing a holiday consisting of Instagrammable steampunk outfits, Silicon Valley networking meet ups and EDM desert raves, rather than engage with the festival’s founding principals of decommodification, radical self-reliance, and civic responsibility.

As

, who first broke the story for The Guardian observed, the protest symbolises just how far the Burner subculture has drifted from its anarchic, activist roots, representing a “cultural moment when the counterculture became protested as part of the problem”.Burning Man’s (d)evolution from provocative, heartfelt subculture to trendy lifestyle aesthetic is endemic of modern cultural movements, which often start out as ideological collectives, but as they grow in popularity, are eventually stripped of their original ethos. Detached from their underlying beliefs, they are reduced to an anaesthetised, but more easily marketable and adoptable version of their former selves.

It’s perhaps surprising to discover that some of the most influential and recognisable visual aesthetics of the past decade were originally rooted in much deeper sociopolitical statements, erupting from feelings of frustration, anger and alienation towards hegemonic social, economic and political structures.

Take for example the Vaporwave aesthetic that hit the cultural zeitgeist in the noughties, with its nostalgic references to 80's and 90's consumer culture, aimed to critique capitalism and the commodification of nostalgia (the name itself inspired partly by Marx's theory of “waves of vapor”). Or the Health Goth movement, cultivated as a philosophical (albeit very lofty) statement about body-mechanized cyborgian humanity, relying on “an anti-nostalgic dystopian present". Or the Art ho movement of 2010s, primarily driven by non-binary PoC’s, leveraging Tumblr as a catalyst for true creative freedom.

But these deeper sentiments and ideological leanings were quickly forgotten as they rose in popularity and bubbled up into the mainstream. Eventually the subcultures reduced to a surface level aesthetic appeal, their mainstream adopters more interested in the way the subcultures looked, less interested in how they felt, or what they wanted to express.

An emotional numbing takes place, the spikes of the subculture removed, its rough and provocative surface glossed over, maximising common appeal and reducing obstacles to entry.

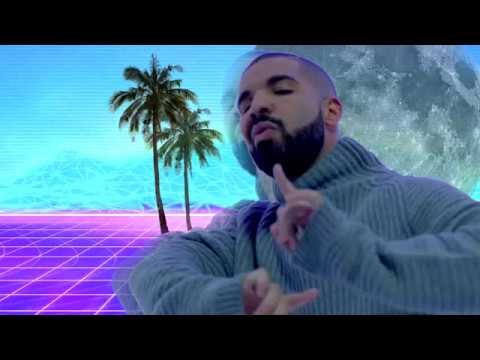

And so through this emotional numbing, Vaporwave’s political leanings were erased, the term reduced to a shorthand for a certain visual style featuring retro CGI, minimalist neon pastels and echoes of 80’s lounge, adopted by Drake's video for "Hotline Bling" and Kanye West's album covers.

Today, Health Goth lives on as the black athletic wear and interweaving of gym clothes with PVC and stainless steel, most notably adopted by the likes of Balenciaga and adidas Y-3.

Meanwhile, the ‘Art ho’ movement was eventually whitewashed, co-opted by Instagram influencers, the look rapidly copied online and by retailers.

The same goes for the ‘Burner’ subculture, its affronting and controversial liberal leanings numbed, it’s post-apocalypse Mad Max aesthetics repackaged for VCs, tech founders and crypto bros looking to temporarily cosplay a solarpunk future. The event is now a theme park offering escapism with a dose of hedonism, without the expectation to commit to the sense of frustration and alienation that underpinned the original subculture.

In today’s era of “microtrend exhaustion”, cultural participants have access to a limitless kaleidoscope of subcultural references to select from. While previous generations had to align to one subculture and exclusively adhere to all its visual and social cues, today we can pick and choose with total freedom and flexibility. As thealgorythm observed on TikTok, today’s cultural participants download, wear and eventually dispose of these cultural markers the same way we use replaceable ‘skins’ in video games. Switching between the exotic aesthetics of Burner culture and the sensibilities of your back-at-home San Fran preppy identity is just one cosmetic change away.

Today, we treat subcultures like a menu, in order to build a tailor-made visual mosaic, rather than distinct, exclusive tribes with singular dogmas dictating what to believe, how to behave and how to look. This shift already started with the rise of the internet, with a more interconnected society removing that need for intensely localised scenes, which often coalesced around a single record or clothes shop or a particular club, location or band.

Today, people are also less willing to commit emotionally to one subculture. For younger demographics in particular, identity is no longer a singular concept. As

noted in a piece exploring the differences between Gen Z and Millennials:Gen Z is better able to treat culture as a playground with less self-conscious dissonance because it’s not as central to their identity formation as it was for [millennials]. For them, the digital is the mainstream. And it’s disposable.

Indeed, many cultural anthropologists argue that the idea of dogmatic, tribal subcultures died decades ago. In a piece on youth culture for Apollo magazine, Peter Watts argues that there have been no unique youth tribes since emo and Nu Rave in the mid 2000s. The kind of subcultures fuelled by total allegiance, governed by a very specific set of social rules and ideological beliefs, and because of this staunch commitment, were often despised, feared or mocked by the general public.

On highway 447, in the middle of Nevada's Black Rock Desert, the standoff between the old-guard counterculture of Burners and the neo-counterculture of eco-protesters represented a clash between a subculture and an aesthetic. On one side of the barricade, a long snake of luxury RVs transporting temporary subculture cosplayers. On the other side of the barricade, Extinction Rebellion, Rave Revolution, and Scientist Rebellion, collectives who resemble perhaps the closest thing we have to a true subculture today. As a collective they remain spiky, rough and confrontational, not yet anaesthetised. They have not yet been packaged into an eco-protester-core aesthetic. The punk ethos of an emotional subculture still shines through.

~ Footnotes ~

Burning Man attendees roadblocked by climate activists: ‘They have a privileged mindset’ | the Guardian

Is youth culture a thing of the past? | Apollo Magazine

What Health Goth Actually Means | The Fader

How Vaporwave Was Created Then Destroyed by the Internet | Esquire

Drake - Hotline Bling | Music video

The whitewashing of the 'art hoe' movement | Diggit

#Arthoe: the teens who kickstarted a feminist art movement | the Guardian

Trends are dead | Vox

Man I have felt this for a while but never seen it put it into words.

There are still preppers and people who are interested permaculture... which as you said are the types who protested burning man...

I think next is the totally homogeneous star trek life where we are all in tracksuits and use the Holo deck now and then!

Great article!

This is an excellent piece.