What makes a neighbourhood? Air Mail recently published an 'ode to the Downtown', a celebration of lower Manhattan, asking it’s most iconic inhabitants to weigh in on the question:

“smells like rotting fruit and garbage in the summer, stale beer, and burning garbage drums in the winter”

“a precise ratio of leashed dogs to prams to scaffolding to cobblestones; mixed with the useless horns of tunnel traffic and the low angled afternoon light sliced thin into street and sky”

“Layers. Beautiful layers of history, people, activity … connected and thriving uniquely.”

“Where the old order breaks down and the new one hasn’t ossified, interesting things can still happen”

The picture that emerges is one of loud and pungent disorder. Bustling bars, vibrant restaurants, side streets filled with arguing neighbours and lovers quarrelling. A love letter to the cacophony, chaos and stench of perfectly imperfect spaces. It’s an ode to a neighbourhood that is distinctly alive, filled with creativity, excitement and mischief.

But it’s also a type of neighbourhood that is increasingly dying. In the rubble, a different blueprint is emerging.

On the northern end of Charing Cross Road in London, squatting over an entrance to the new Tottenham Court Road station, is Soho Place, a £300m mixed-use development, twelve years in the making. The facade is encased in a huge digital screen, advertising the programme of the theatre, which has been branded @sohoplace, as if permanently trapped on Twitter.

On the other side of the road is the "Outernet" - £1bn reinvention of an entire urban block, a complex of live venues, and the “Now Building” - consisting of a gigantic walk-in billboard.

The Outernet also houses a luxury Chinese restaurant, that esteemed restaurant critic Grace Dent summarised in a scathing review as an "Instagram content fulfilment hub".

The project is billed as “the future of immersive brand storytelling”, ready to serve “unrivalled experiences that drive maximum impact and awareness”. And just as brands so often annex, sanitize and repackage subcultures in pursuit of relevance, these neighbourhoods-as-brands transform what was originally lively, diverse urban communities into securely controlled and decontaminated user experiences. As Oliver Wainwright describes in his tour of the Outernet:

[The guide tells me] “we’ve created a matrix of private streets that we can shut down as we wish.” He leads me down an alleyway that connects to the venues and to his music-themed hotel, Chateau Denmark, where another LED-screen-lined tunnel leads to Denmark Street. Every entrance to the block is flanked by security guards and gates that can be closed at will, making the place feel somewhat less like the free public space he described.”

In these new urban redevelopment projects, each consumer touchpoint is designed for efficiency, like a sleek mobile app, resembling something that would germinate in a brainstorm between a digital agency, a starchitect firm and McKinsey.

Whole new cities are currently being designed based on this blueprint.

A few examples include Chengdu Smart City in China, BiodiverCity in Malaysia, and Bitcoin City in El Salvador. The most discussed - and perhaps most ambitious of these projects - is NEOM in Saudi Arabia. The initiative’s flagship is ‘The Line’ a 150-storey, linear superstructure that will stretch a hundred miles across the desert, with less than the distance between two New York City avenues separating them, promising “zero-gravity urbanism”. Another planned ‘region’ in NEOM is called Trojena (which Henry Grabar at Slate aptly points out sounds like an erectile dysfunction medicine). Trojena will be made up of six districts, with aggressively generic names: Gateway, Discover, Valley, Explore, Relax, and Fun.

But away from these multi-million urban developments - projects guided by coldly calculated data points and fuelled by techno-optimism - there’s another type of urban utopia. Experiences shaped instead by creative constraints and bottom-up community involvement.

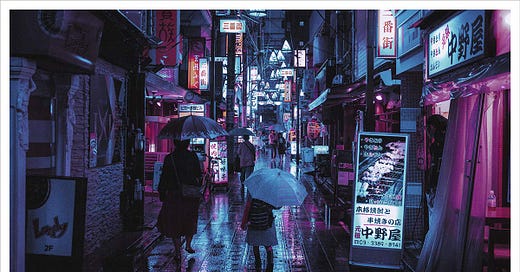

One example is Tokyo - arguably one of the most vibrant and livable cities on the planet - a place that somehow remains intimate and harmonious despite its megacity status.

The book ‘Emergent Tokyo, designing the spontaneous city’ documents how the Japanese metropolis is in many ways the ultimate testament of permeable, inclusive, and adaptive urban patterns that require neither extensive master planning nor corporate urbanism to develop.

A demonstration of this is ‘Yokochos’ - alleyways tucked away and hidden from main streets, tiny buildings that have survived decades of intense re-development pressure from corporations, that to this day act as the backbone of neighbourhood life in a sprawling megacity. As

frames it, a third place, filled with snack shops, restaurants, and tiny bars, packed with locals and visitors alike, the same charm from 50 years ago noticeable in the air.Neighbourhoods-as-brands, with their labyrinths of streamlined and tightly controlled, LED screen-clad alleyways, seamlessly connecting experiential touchpoints, undoubtedly feel sleek in 3D renders and jargon-filled marketing material. But they are a sign that its designers have lost touch with how everyday residents inhabit spaces. Neighbourhoods are not consumer journeys with pain points, with every corner and surface an opportunity for technological innovation. Some of the most well-functioning cities are messy, their infrastructure improvised and imperfect, rather than meticulously planned and strategized. A chaotic hotbed for unbridled creativity and heart-warming human interactions.