idle gaze 020: in transit - the role liminal spaces play in culture.

The lonely landscapes of Burial, quiet corridors of the Park Hyatt Tokyo and an empty mall edit of Toto’s Africa: how the world of music, film and photography are drawn to eery emptiness.

In 2020, mysterious videos and images of abandoned, empty spaces - a suburban shopping centre at 4 am or a school hallway during summer, a deserted swimming pool, anonymous corporate backrooms with grey carpet and fluorescent lighting - begun to infiltrate the TikTok algorithm. They were tagged with #liminalspaces - a hashtag that has now reached over 100 million views on the platform.

The trend had been percolating for a while in the dark forests of the web - the @spaceliminal bot – which regularly tweets liminal photographs – already had 148,000 followers. r/liminalspace has been an active subreddit since the noughties.

But liminality - a more melancholic, and sometimes sinister sibling of nostalgia - goes beyond TikTok and online communities, having played a wider, influential role throughout the history of music, design, art and cinema.

In architectural phraseology and art theory, liminal spaces are often defined as “the time between the 'what was' and the 'next'', or “a place of transition, waiting, and not knowing”'. Often, a liminal space isn’t so much a place, but a feeling. It’s almost always mundane and instantly distinguishable, yet triggers a universal sense of discomfort. The content characteristically radiates an eeriness, evoking memories you can’t quite put your finger on, but that provokes a very visceral, emotional reaction.

In music, the lonely vibrations of liminality have become a rich source of introspective expression. Burial - one of the most disruptive electronic artists of recent times, redefined the course of a whole genre by tapping into a deep feeling of liminality that would capture the hearts of millions of listeners.

Rather than producing dance music, Burial’s albums capture a particular introspective feeling associated with dance music. They feature off-kilter rhythms, pitched and darkly poetic vocal tracks, filled with sorrow and loneliness. Listening to his Mercury Prize-winning masterpiece Untrue feels like leaving a rave at 5 am, walking through empty South London streets, the reverberations from the music still echoing in the distance. There’s a distant spectral quality to the sound, the sensation of being close enough to feel the energy, yet far away enough as to still feel like an outsider just passing by.

Will Bevan (Burial’s real name) never took a step into a club before he started producing music, but growing up his brother would visit his bedroom early in the morning and play him mixtapes from his nightly escapades into the 90s UK rave scene. Hua Hsu at The New Yorker observed that Bevan’s secondhand experience shaped the voyeuristic aspect of his music:

...it always feels as if you’re lurking, or just drifting through a scene. Nevertheless, he managed to capture something essential about the draw of nightlife, particularly for lonely and despairing oddballs.

To test to see if his tunes would evoke this deep-down, almost supernatural sensation he aimed to create, Bevan would reportedly drive around South London in the dead of night, his tracks blasting through the car’s sound system, as he gazed out the window at the derelict streets, checking for the quality of ‘distance’ that he sought.

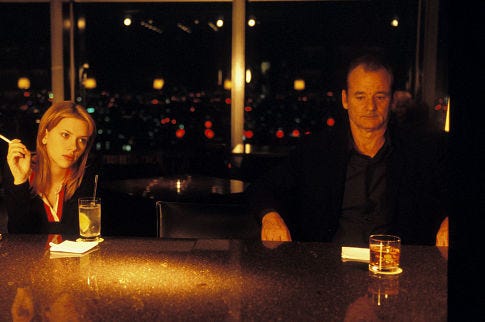

In cinema, spontaneous encounters and fleeting romances blossom in liminal spaces. 20 years ago, Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation fuelled a whole generation’s obsession with hotel lounges and meet-cutes in foreign lands.

Lost in Translation is essentially a film about liminality. Over the course of the film’s 105 minutes, Bob and Charlotte, two Americans abroad in Tokyo, lunch at desolate shabu-shabu restaurants and stare out from midnight taxis at the bright lights of Shinjuku. Most famously, they walk around, sleepless, down the muted green corridors of the Park Hyatt, crossing paths at the New York bar, the hotel’s downcast yet welcoming top floor watering hole, frequented by lonely drinkers and passers-through. The iconic hotel acts as a fortress of solitude in a foreign land - exotic, yet strangely familiar.

When Coppola was asked why she picked the Park Hyatt as the main set for the film, she noted its liminal peculiarity. A space made up of many recognizable elements, but re-shaped and pulled out of context, creating an every day, yet very otherwordly experience:

It’s just one of my favorite places in the world. Tokyo is so hectic, but inside the hotel it’s very silent. And the design of it is interesting. It’s weird to have this New York bar…the jazz singer…the French restaurant, all in Tokyo. It’s this weird combination of different cultures.

Liminality is often explored by our deep-rooted memories of public spaces. Liminal space mood boards are filled with pictures of empty malls we all seem to recognize from our childhoods. On Youtube, there are hundreds of mall edits - Songs, ranging from Toto’s “Africa” to Childish Gambino’s “Redbone”, injected with a heavy dose of reverb, as to sound as though they’re playing out from the speakers at a cavernous, abandoned shopping centre.

Attempting to explain the immense popularity of mall edits, Jia Tolentino suggested they take us back to nostalgic memories of places where someone else controls the music—in a crowd, or at a mall, or in a pounding bathroom, “someplace where you’ve taken the chance of being lonely in public, instead of retreating and clicking around alone.” They are the most literal musical translation of liminality.

Why are liminal spaces the source of such rich creative fodder? There seems to be something in the solitude and moments of introspection found in places of transition, in waiting, and not knowing, which open us up for momentary, but profound interactions. These liminal spaces allow us to become emotional tourists, letting alien sensations take hold of us for a second, safe in the knowledge we are only passing through.

Idle gaze is a newsletter written by Alexi Gunner, a strategist based in Berlin. If you’ve enjoyed this edition, please consider forwarding it to a friend. If you’re reading it for the first time, consider subscribing (it’s free!)